National concern over soaring prescription drug prices has recently cast a spotlight on the use of generic drugs to save money and on various drug industry practices that critics say keep generics off the market as long as possible.

In fact, some lawmakers are now touting generics—less costly and less promoted than brand-name drugs—as a way to ease the troubled path to a Medicare drug benefit.

House Republicans drafting a new benefit proposal are considering lower copayments for patients who choose generics, a practice increasingly used in private health plans to keep costs down.

| "The pharmaceutical companies have looked for every loophole they could possibly find to keep generics off the market." |

Up to $10 billion a year could be shaved from the cost of a benefit in this way, according to a recent study from Brandeis University. "How can we get more bang for our buck? The number one answer, as this study shows, is generics," Sen. Charles Schumer, D-N.Y., told reporters.

Promoting generics through incentives and education could bring down overall costs without imposing price controls on drugs, which the industry has always resisted.

GIVING GENERICS A BREAK

At the

same time, several influential groups with widely diverging

viewpoints—including legislators, state governors, major employers, unions

and health plans—are pressing to close "loopholes" in a 1984 law that

allow brand-name companies to delay generic competition.

The brand-name industry fiercely opposes such moves. But the National Governors Association, citing the impact of drug costs on state Medicaid budgets, has urged Congress to "fully review" the law.

Generics are "copycat" drugs that become available when patents held by brand-name companies expire. They are less costly because generic drugmakers do not have to recoup the costs of research and development. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) must approve the copies, ensuring they work the same way medically as the original drugs.

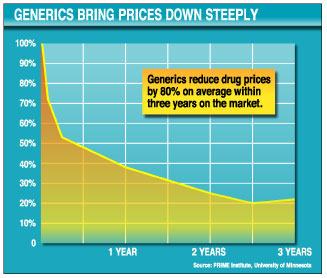

When generics enter the market, prices drop dramatically, falling on average to less than 50 percent of the brand-name price after six months and to about 20 percent within three years. (Brand-name prices tend to remain high, experts say, as companies rely on promotions to maintain brand loyalty.)

Patents on about 17 brand-name medicines are due to expire in the next five years, including blockbusters Prevacid (for ulcers), Zocor and Pravachol (for cholesterol) and Zoloft and Paxil (for depression). Each of these generates sales of $1 billion to $3 billion a year.

A key issue, though, is how soon generics can come to market. The 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act speeded up that process to increase generic competition, while allowing brand-name companies longer patent protection to encourage research and innovation.

But Rep. Henry Waxman, D-Calif., who co-authored the act with Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, now says: "The pharmaceutical companies under this law have looked for every loophole they could possibly find to keep generics off the market."

Schumer and Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., are cosponsoring a bill to close these perceived loopholes. Waxman supports it but adds: "I always fear that if we open up Hatch-Waxman [to any changes], the brand-name companies would try to grab more for themselves."

The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), the lobby group for brand-name companies, interprets moves to change the law as an attack on medical research. "They would seriously erode the incentive and protection for innovation that enables new drug development," Richard I. Smith, PhRMA's vice president for policy, told reporters.

The generic industry's lobbying group, the Generic Pharmaceutical Association, disagrees. "Nobody's trying to override patents," says spokesman Clay O'Dell. Once patents expire, brand-name companies should be moving on to new products, he says. "But they spend money and effort on a drug that's already on the market, trying to keep a monopoly."

PhRMA says the effective exclusivity period of brand-name products—the time between market launch and the expiration of the patent—averages about 12 years. But sometimes it is much longer.

GAMING THE PATENT PERIODS

"A

pill is not always protected by just one patent but anywhere from three to

30 patents," says Stephen Schondelmeyer, director of the University of

Minnesota's PRIME Institute, which tracks drug trends. Besides patenting

the drug's active chemical entity, he says, companies over time also

patent "different dosage forms, uses and every process by which they make

it." In this way, he says, some drugs get "a total patent life of 25 to 30

years, which is not what Congress intended."

| In some cases, brand-name companies have paid millions of dollars to generic manufacturers to hold off. |

Under the 1984 law, brand-name companies are also able to delay approval of generics through court action by up to two and a half years after a patent expires. And in some cases they have paid millions of dollars to generic companies to hold off.

A Federal Trade Commission investigation into anti-competitive agreements in the drug industry documented collusion. In one case, a brand-name company paid a generic company $4.5 million a month to delay competing for six months—during which time the brand was expected to generate $185 million in sales. In another case, a brand-name company paid $60 million to one generic manufacturer and $30 million to another to delay their versions of its drug.

As another example of the way brand-name companies pursue patent extensions, critics point to a 1997 law that gave them a big incentive to test drugs for use by children.

For decades the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and others had urged companies to make such tests so that precise dosages and side effects could be established for children. "But all efforts failed and by the mid-1990s only 11 studies had been accomplished," says Robert Ward, M.D., former chair of the AAP Committee on Drugs.

The 1997 law, also sponsored by Waxman, offered companies a further six months of exclusive marketing rights, after patent expiration, in return for pediatric testing. It worked. Within three years, 332 new pediatric drug studies were begun.

But when the law was due for renewal last December, Waxman told fellow committee members that the exclusivity clause had given the companies an unintended "windfall" of billions of dollars at the expense of consumers who were denied six months of lower generic prices.

He cited the case of the heartburn drug Prilosec, noting that pediatric testing had cost its maker, Astra-Zeneca, an estimated $2-$4 million but had reaped $1.2 billion in extra sales—more than "the entire budget of the National Institute of Child Health," he said, and "between 30,000 and 60,000 percent return on the company's investment."

DRUGMAKERS AND LOBBYING

Waxman

put forward an amendment which, instead of six months exclusivity, would

have paid the companies twice the cost of testing. "I thought that was

pretty generous," he says. But it failed because, he says, "the

pharmaceutical companies did an excellent job lobbying."

PhRMA spokesman Jeff Trewhitt says: "Our view is that this law has worked well, as the numbers of tests prove. If it ain't broke, why fix it?"

The FDA estimates that, because access to generics is delayed, the pediatric incentive will cost consumers $14 billion over 20 years. This, it says, adds just "one-half of 1 percent to the nation's pharmaceutical bill."

"But that is much more than 0.5 percent to seniors who have to continue paying the brand-name price," says Schondelmeyer. To them, he says, "it's at least a 50 percent difference for those six months."

Also, read Ads, Promotions Drive Up Drug Costs, the first article in the AARP Bulletin's "High Cost of Drugs" series.